In the future there will be no one like you

August 7, 2022

We both thought you would die first. I don't remember when we had the conversation (I wish, almost every day, that I remembered you better) but it would have come up naturally. I remember you telling me that your favourite writer, Lois McMaster Bujold, had said that your favourite character, Miles Vorkosigan, dies young. Fifty-five, if I remember correctly. Fifty-five would have seemed old to us, when we were twenty-five.

There were many reasons you loved Miles. He was a lot like you, the quickest thinker in any room, an adherent to a code of honour despite how anachronistic that seemed to his friends, able to do just about anything he set his mind to, unless his body refused. You said he was the first character you read who was like that: perfectly able if he stayed vigilantly within certain physical restrictions, and trying desperately to compensate with cleverness when he went outside them.

You were not ready to die, but you were more sanguine about the possibility than anyone else our age. You’d had two open heart surgeries before you were ten. Survival rates were getting better every year, but you still risked a double-digit chance of death each time the surgeons opened up your chest. You told me about a blurry childhood memory of lying in hospital, hemorrhaging (though you wouldn’t have known that word) after a surgery, and asking your mom if she could hold your blood in your chest.

I heard some of these stories when we talked about having kids together. You were certain you didn’t want to pass on Holt-Oram Syndrome. It’s caused by a mutation in TBX5, a fetal transcription factor, so its severity varies, but there are always skeletal abnormalities and heart problems. Your left thumb wasn’t opposable, your cardiologist forbade you from jogging, and you rejected all my suggestions of fashionable shoes because they didn’t fit your orthotics. Other people with Holt-Oram are born without an arm. It’s an autosomal dominant condition, so if we wanted to have biological children we’d need to do preimplantation diagnosis or (if the technology was ready in time) CRISPR gene editing.

I felt uneasy about both options. Aren’t expensive reproductive technologies a repugnant manner of encoding inequality in our genomes? Can we trust ourselves to make good judgments about which sorts of people we want to bring into the world? All the inhumane human history of forced sterilizations and ethnic cleansings suggests otherwise. So much of what we consider disability is caused by the intolerance of an unaccommodating society, not something wrong with disabled bodies or minds. What if we excised a ton of wonderful potential people from the future, based on criteria that would horrify our descendants?

Your counter-argument was elegant: with certain syndromes, Holt-Oram among them, there are no adults alive with an unaltered version of the bodies they were born with. You either live through surgeries as a child, changing your body, or you die. If no one can survive into the future without medical intervention, then why object to moving the treatment before birth?

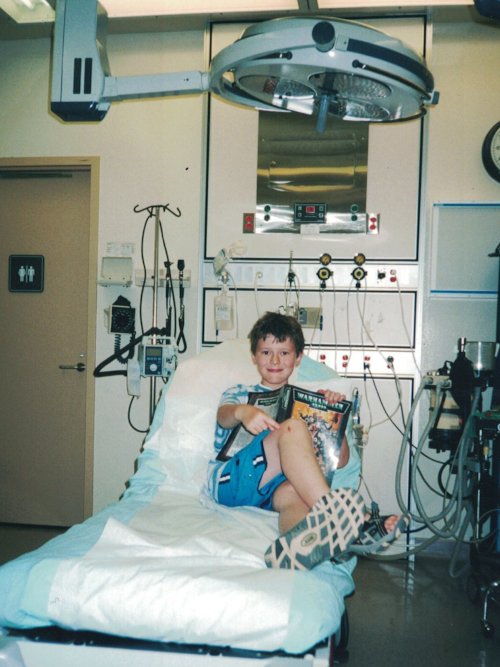

You, sitting in the hospital, long before I was able to meet you. You spent so much time there that the nurses would call your parents to ask what toys they should buy for the playroom.

It was one of the many times you changed my mind. You knew how to structure an argument that would coil around my desire for justice and consistent principles and convince me in an instant (though, as usual, I don’t think I admitted you were right until the next day). I think you were right: heritable genome editing can be a form of treatment.

If I examined the worry underneath all my more flattering concerns, I suspect I’d have found this: what if there aren’t people like you in the future?

Well, in a way, there won’t be. One of the first texts I sent after you died was: I will never meet any children with Zach’s face.

…

When I started writing this essay, it was a magazine pitch about eugenics and the tension I felt between dearly wanting heritable human genome editing for us but not being sure I wanted it enough to unleash it on our species. After you died in a bike accident, in a way that was probably unrelated to your mutated genome and the broken heart it gave you, I was looking through my notes and found this title:

in the future there will be no one like you.

It means something a little different to me now.

I try my best to be someone like you, to remember the sorts of arguments we’d have and the sharper sense of goodness you would give me, and to bring it into the future. But that is such a feeble salve on the loss. You died, and all those arguments about what to do with our combined genomes became suddenly less relevant.

We will never launch a charter challenge against the Assisted Human Reproduction Act to let us gene edit your copy TBX5, which we’d toyed with as a sweet little legal legacy of our relationship. I can’t imagine doing something like that, or even half-joking about doing something like that, with anyone else.

Edna St. Vincent Millay says it well:

Lovers and thinkers, into the earth with you.

Be one with the dull, the indiscriminate dust.

A fragment of what you felt, of what you knew,

A formula, a phrase remains,—but the best is lost.